How to write science fiction

Want to write science fiction? Matthew de Abaitua shares his advice on creating strange new worlds.

[rt_reading_time label="Reading Time:" postfix="minutes" postfix_singular="minute"]

Start with the idea

Science fiction starts with the idea or what Dario Suvin calls the novum: the new thing. This is a device or premise that is scientifically plausible and which focuses the difference between the reader’s world and the fictional science fiction world. And it’s new, or you’ve found a way of making it new.

H.G. Wells founded modern science fiction with two novums; a time machine and, in The War of the Worlds, a Martian. A novum is not a magic ring, or a wand: these are magical objects and belong in fantasy. A novum belongs to the same hypothetical way of thinking as a scientific experiment.

Expose characters to your idea

How does your idea affect people? Technology is changing us and the world we live in. Tell us a story about it.

In literary fiction, character is the animating force of the narrative. Particularity of character, what has been called ‘depth of character’, is a way of measuring the moral insight of the author.

I teach Writing Science Fiction to undergraduates at Essex University. My favourite workshop exercise is to get the students to devise a novum or idea and then I ask them to choose – at random – a character which I have prepared on a Post-it note, characters as simple as ‘lost child’ or ‘celebrity and entourage’ or ‘dying architect’. The student’s imagination must work to reconcile the novum with the random character. Creativity is, at its core, problem solving and it is more responsive to limits than to the blank page.

Be plausible

Nods and winks to the composition of the text, so modish in the 1990s, are uninteresting to me. Postmodern pranks are particularly fatal for literature of the fantastic. You want the reader to marvel and shiver at the strangeness of your vision. The prose must ring with clarity and conviction and not contain cute in-jokes or alibis.

We can explore this rule via an exception. (All my rules are – like the Post-it notes – arbitrary parameters for creativity to rub up against). Rudyard Kipling wrote an excellent ‘scientific romance’ concerning airships delivering intercontinental mail. The story With the Night Mail took the form of journalistic reports. These were originally published alongside adverts also written by Kipling, for products manufactured in his invented future society. He put this innovative form to the service of believability, transferring the ‘truthiness’ of newspaper reporting to his fantastic tale.

Another easy way to make a story appear plausible is to deploy what I call Spiner’s Precedent, or It Is Happening Again. This is a technique named after Brent Spiner’s role in the film Independence Day. He plays a scientist in Area 51 who explains to the heroes that this is not the first time the aliens have visited, and the last time they came, they left behind a spaceship.

Spiner’s Precedent does two things. One, it sets up a history to your novum, adding plausibility. Two, it provides a character who can provide exposition about the aliens and their intent, without having to ask the aliens themselves.

Have the confidence of your own strangeness

Have the confidence of your own strangeness

The universe gets very weird at the quantum level, or in the singularity of a black hole. As our understanding of our solar system deepens, so we can appreciate its strangeness: the lead rain on the hilltops of Venus, the deep ocean beneath the ice of Jupiter’s moon Europa, or the Oort Cloud, trillions of objects at the very edge of the sun’s influence.

I like strangeness, what the German critics call the unheimlich or the unhomelike; that is, something familiar rendered peculiar by subtle differences. Science fiction that strays too far from the familiar sacrifices this ancient frisson.

The robots are already here

Robots replace workers, and they always have, ever since a sorcerer first summoned a golem to clean up his lair.

Think of all the people in the public service you encounter across the course of your life: midwife, nursery assistant, nanny, primary school teacher, youth worker, fireman, policeman, lawyer, parole officer, prison officer, doctor, surgeon, palliative care nurse, undertaker. Then replace them all with robots, many different mechanical bodies but all guided by one cloud-based intelligence.

In this world, the machine gaze that first greets you when you come into the world will be the same diffident, algorithmic mind which lowers you into the earth.

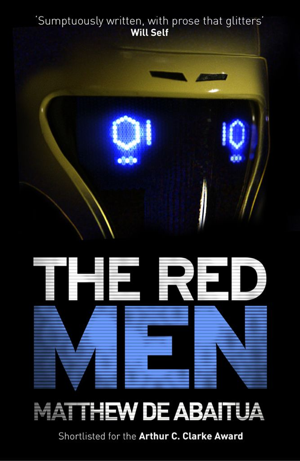

For my novel The Red Men, I invented a robot called Dr Easy. It is covered with soft leather so that if you want to beat it up, it won’t graze your knuckles. The intelligence of the robot is in the cloud and so the bodies themselves are mass-produced, lightweight and disposable. Much like the military drone.

So is artificial intelligence

Google trains its algorithms through exposure to our wants and desires but its all one-way traffic. It is likely that artificial intelligence will be unintelligible to humans. Explore James Bridle’s curation of The New Aesthetic to understand the strange interventions of the algorithmic and digital into what we may nostalgically call the real world.

Virtual reality is over. There will not be a separate digital realm. Digital will be overlay and underlay to the everyday, and we are being changed by it, whether we want to be or not. Just as a letterbox determines the size of an envelope, so the search box will determine the shape of our desires.

What about aliens?

I’m not interested in aliens and every indication is that the feeling is mutual.

This article first appeared in Publishing Talk Magazine issue 5.

Thanks for taking the time to respond, Holly. Science fiction is hybrid, mixing up horror, fantasy, crime etc so it can sometimes seem that an SF work actually has magic at its core. Like Star Wars, for example. But I would maintain that Star Wars is more fantasy than SF, being predicated on magic and the Force, and being set a long long time ago. No-one gets points for genre purity, of course, but I draw these distinctions when explaining the difference between the traditions to students:

Science fiction – could happen but not right now.

Speculative fiction – might happen now.

Fantasy fiction – could never happen.

Really enjoyed reading this – some great ideas.

One question remians with me, though: Does the central theme of science fiction have to be “scientifically plausible”? I’m not so sure…